| KALI Text and Research by Anna Pirera for www.ilcerchiodellaluna.it Translation by Katiuscia Cancedda translatethis1@yahoo.co.uk |

Vai alla versione italiana |

Come, Mother, come!

Because Terror is your name,

Death is in your breath,

And the vibration of each of your steps

Destroys a world for ever. Come, Mother, come!

The Mother appears

To those who have the courage to love pain

And embrace the form of death,

Dancing the dance of destruction.

Vivekananada

Kali is probably the most popular Goddess in the Hindu pantheon; she’s the Goddess of the active and disruptive feminine energy, by unrestrainable power, heir of the ancient Goddess of death and transformation. Among her names we have: Bhairavi, the frightening; Chamunda, the killer; Jari-Mari, the hot-cold.

Kali is primarily the active Goddess, a feminine that is strength, one aspect of Shakti, the Goddess of energy and change. It’s vital to stress that in Hindu’s philosophical and religious thinking, masculine and feminine archetypes appear in many opposite ways compared to our culture: passivity belongs to the male and Gods, whereas active and expressive tasks belong to the female and Goddesses.

India is one of those rare places in which the Goddess is still present and venerated in our time: She appears to Hinduism with many faces and various forms, though remaining some how the one, the ancient Goddess, Devi (1).

Under the name Shakti, she governs material energy, active, creative, perennially in motion.

As Parvati, she represents the primal principle manifest in the world.

As Durga, warrior Goddess, she meets us impetuously and powerfully.

As Radha, she’s the divine love, essence of every relationship, power of pleasure.

As Saraswati, she sings the creative sound of the divine creation.

She yet manifests with many other names: Sita, Tara, Gayatri, Sati, Uma, Aditi...

Finally Kali, the most famous, as already mentioned, the most mysterious, the most intense, and the most adored.

Kali’s faces

Kali, of undisputable impact, with whom even the most rational, even the coldest of people would be involved, engaged deeply. It only takes to enter once in one of Kali’s temples, maybe Khaligat in Calcutta, or in Kathmandu, from which the image on the left comes, of one holding a wrathful Kali – though we’ll also see her in pacified forms – not to ever forget her.

Kali, of undisputable impact, with whom even the most rational, even the coldest of people would be involved, engaged deeply. It only takes to enter once in one of Kali’s temples, maybe Khaligat in Calcutta, or in Kathmandu, from which the image on the left comes, of one holding a wrathful Kali – though we’ll also see her in pacified forms – not to ever forget her.

If the temple is crowded, packed with people, women, men, children, as it often happens there, you must push through, find space, wait and let the crowd carry you through the corridors, so that, when you suddenly find yourself in front of Her, the surprise blends with the impact. Otherwise, if it’s a minor temple, or a calmer time, you can arrive pronto, even too quickly, in front of the Murti (2), of the Goddess who’s already there, not only in Her image but in Her Presence.

In both cases, you’re overwhelmed by a world of scents and spices and flowers and above all, intense, the pungent smell of the red kettle and that nauseating of animal blood. Rivers of red poured over the Black Goddess, at Her feet, flowing to the basements, on Her limbs, on Her tongue. The power of Her arms, the outline of Her necklace’s skulls, Her gaping mouth. She is black, towering, striking.

No chance for those standing before Her. An encounter with no discounts, no mediations, with themselves and with Herself, as if they were one and, at the same time, the encounter with what is more alien and obscure – with terror and nameless fear.

Kali forces you to complete nudity, to an encounter at the mirror, and for this characteristic she’s also at the core of the tantric spiritual path. She represents the breaking of every pattern, of every preconceived form; in fact, in the tantric cult, the devotee is invited to break all current prohibitions and social taboos one by one including eating corpses.

As opposed to the Murti’s side, when Kali appears on her irate form, Ugra, she doesn’t look up avoiding eye contact with anyone; she’s not able to see the individual, she’s pure energy, at least until she reaches her breakpoint, until she reaches the reconciled form.

And from what I called “breakpoint”, Kali’s other face emerges, the one that can be met in temples and that is presently the most common one: the blessing Kali, the protective Kali, Kali-ma, the Mother to whom wonderful chants of praise and offerings were dedicated by the mystic bhakta of the 19th century.

And from what I called “breakpoint”, Kali’s other face emerges, the one that can be met in temples and that is presently the most common one: the blessing Kali, the protective Kali, Kali-ma, the Mother to whom wonderful chants of praise and offerings were dedicated by the mystic bhakta of the 19th century.

By reversing her principal attributes, She appears here smiling, benevolent, young, sometimes even light skinned. She can be invoked against natural calamities, hurricanes, cataclysms.

This is Kali’s form that can enter the houses – the Kali ugra could be too powerful, too dangerous. She has the face of the protector of the household, of the family.

As Goddess and as Mother, She destroys to transform, to purify and to finally welcome the devotee to her luminous energy as Shiva’s Bride.

Some aspects of Kali

An important characteristic of Hindu goddesses is their double valence: they represent both the spiritual world and the material one in the feminine form. So Kali, as the others, is the Goddess and a goddess at the same time, the Great Goddess and her appearance as destroying warrior and the energy of the tamas guna, the material principle behind every transformation.

With reference to material energies, Kali is part of a trinity of goddesses that reminds very much of the threefold goddess in some of her forms of the Mediterranean and European area. There are numerous temples dedicated to such goddess: Lakshmi, Saraswati, Kali, corresponding to the three primal energies (gunas): the energy of creation (rajas – Saraswati, the rising moon), the energy of conservation (sattva – Lakshmi, the full moon) and the energy of disillusion (tamas – Kali, the black moon) (3)

Kali is therefore the ‘dark’ face of the threefold, corresponding to the black moon, to the energy of death, of sleep, of illusion and of the match ignorance-mysterious knowledge. Kali is the form representing also the power of transformation, which is always death power, and for this reason she’s associated with snakes.

Due to her dark face, Kali belongs to the world of the double Goddess: the one honoured in many villages in the simple form of a round-shaped stone painted in ochre-red, like the pair Parvati-Durga/Kali. They display a luminous face, clear and attractive in Parvati and dark, black and disturbing in Durga-Kali.

In India, deities can be divided in “warm” or “cold”. The former express the characteristics of pride, of rage and war: they are terrifying and furious divinities requiring sacrifices – of blood – to calm down. The latter are gentle and familiar goddesses who nourish the communities with tender love.

The radical feminism interpreted Kali as the manifestation of the feminine collective unconscious in its rage against the male-dominated regimes. It’s a coherent and consistent explanation with the flaw of defusing Kali to a transitory historic moment, so as to say that she will disappear – will heal – when all parts are balanced and women will get back to be good and kind like in the gylanic legends. As to say that, in the end, only Parvati will remain.

What happened to the primordial energy of the ancient Goddess of Death? No, I think that impoverishing her nature stray us from comprehending what is the divine feminine in its totality.

An aspect that makes Kali particularly interesting is her being a “living” Goddess, still venerated nowadays, with whom we have the opportunity of a live encounter within her myths’ dynamics, her temples, her festivals, rites and relationship with us (in Hinduism, a relationship is an essential aspect of the divine in all its variants – if not the most essential one).

Let’s start a journey into ‘Kali’s world’ through her iconography.

ICONOGRAPHY

Her Image

|

|

|

|

|

Kali is described and represented as:

Black: (in Sanskrit, kali with a short a means “black” and is often mistaken for kala with a long a, which means “time”). Both skin and hair are black, her priests wear black, she’s often represented near black cats and she’s particularly venerated during black moon nights. There are also blue and purple forms of Kali, ‘gentle’ and ‘pacific’ forms of this Goddess with two of her hands in blessing mudra (position) that is venerated in households, although at the outside of the very house there are forms reminiscing those of a pacified Narasimha (incarnation of Krishna-Vishnu).

Naked : Kali’s nudity has been so difficult that an iconography was created representing her with a girdle made out of chopped arms and she often represented wearing a red sari in temples. Originally, though, she was naked, with the vulva exposed, sagging breasts and a swollen womb, wild, ugly.

With ruffled hair down : this is a symbol of sexuality both from an archetypical point of view and from the point of view of the existing Indian social organisation through which it is possible to understand whether a woman is still a virgin, married or widowed by the way she wears her hair. Kali’s is a free sexuality, unrestrained and wild. In literature, the Great Goddess, Devi, puts her hair down whenever she’s angry or called to battle. In the Mahabaratha, the origin of chaos and war and the collapse of civilisation was caused by Pandava’s wife, Draupadi, when she let her hair down, and only ended when she finally washed it in Kaurava’s blood and then plated it up again as usual – in fact, Draupadi turns into Kali during her banishment period in the forest.

With a manly appearance and wearing a garland made of moustached, chopped male heads, on which identities there are various myths and stories: demons, men who sacrificed themselves to her, symbols of a false ego that should be abandoned according to spiritual paths, letters from Sanskrit alphabet – because Kali “chops the head to the word” leading us to what precedes it, setting us free from its bonds. She wears baby bodies as earrings.

Blood-dripping tongue sticking out: in the majority of temples, the blood of sacrificed animals is run through her tongue. Wherever animal sacrifices are forbidden, a mixture of red kukkuma is used instead. Kali is essentially thirsty for blood. The meaning of the hanging tongue associates her to many more representations of “dark” goddesses, among who are the Greek Gorgons and Medusa in particular, with a very ancient iconographic origin: it can also evoke the flowing of the menstrual blood in the association mouth-vulva (a representation of a menstruated Kali is available below). Kali’s tongue is central in her iconography so that the most ancient mentioning of her in the Vedas refers to her as one of the tongues of Agni, God of Fire.

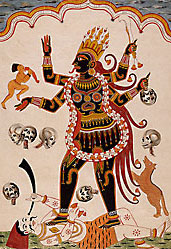

Usually with four hands (even more in some representations), holding in each one:

A bloodied axe and other weapons;

A head – male – chopped and dripping blood;

A dish to collect the blood.

|

|

|

|

Ancient and more recent representations of Kali in angry form, in battle on Shiva’s body.

Moreover, Kali stands on Shiva’s body, represented in Tantrism as sexually active, on top of him – as would have liked Adam’s first wife, Lilith. She’s generally represented “dancing” or moving, a leg lifted up and the other foot on the ground, energy entirely in motion. She’s surrounded by dogs and jackals, lives on battle fields and in crematoriums (where her temples are built) and in places traditionally considered “impure”.

Often she rides a tiger like Durga and is escorted by notoriously combative female cats. Her impact is always strong, undoubted, and an olfactory component is associated to a visual one: black, red, blood. As previously mentioned, entering one of Kali’s temples, encountering Her murti, is an unforgettable experience.

Kali, Shakti and Durga

Kali is associated to Shakti and Durga, both counterparts to Shiva from whom they cannot be separated.

Kali is associated to Shakti and Durga, both counterparts to Shiva from whom they cannot be separated.

Shakti is energy and action, a dynamic force, with no beginning and no end, continuously self-transforming but always remaining the same – it’s the eternal dance of the elements, the movement of atoms and universe. In the majority of representations, she’s depicted attached to Shiva as one body, of which Shakti is the left side. The name Shakti originates from to root shak, meaning potentiality, producing power, and therefore she’s also the Cosmic Mother, or pure generating energy.

Durga , who dresses as a maiden but acts as a killer, is a warrior goddess riding a tiger, fighting demons with her many armed arms. She represents the principles of sex and violence that make the great wheel of life go round.

Kali carries something belonging both to Shakti and Durga, but her symbols are clearly those evoking bhaya and vibhitsa, which is fear and repulsion, leading us to the dark and repulsive aspects of the cosmos – and therefore of the divine – aspects which we tend to deny, inhibit or suppress.

Kali of the origins, heir of the Ancient Goddess

It is as difficult to track down Kali’s history as much as tracing the boundaries of today’s cult, although her origins are probably pre-Aryans, Dravidians. There are indeed figurines of goddesses, amongst the finds of that era, whose energy recalls the one of shaktis and of Kali in particular.

The name Kali appears for the first time on the Aryan Vedas (VIII/V B.C.) in an already patriarchal era, in the Mundaka Upanishad, as the black one among the seven blazing tongues of Agni, God of Fire. An antecedent of Kali’s figure appears instead on the Rig Veda under the name of Raatri, which is considered an ancient representation of Durga. Kali is mentioned on the Mahabaratha, on the battlefield.

During the period overlapping the Christian era, a sanguinary goddess similar to Kali named Kottravai appears in the literature of that period: as Kali, she wears her hair down, draws terror to whom gets near her and she celebrates on battlefields covered with corpses. It is possible that between the Sanskrit goddess Raatri and the indigenous Kottravai may have produced the terrifying goddesses of the Medieval Hinduism. The majority of Kali’s characteristics as we know her today date back to that time.

In Late Antiquity, during the Puran era, Kali was allocated a place in the Hindu pantheon. Kali, or Kalika, was described on Devi Mahatmya (also known as Chandi or Durgasaptasati) by the Markandeya Purana, dated between the 300 and the 600 A.C.): here it is stated that she is an emanation of Durga, a destroyer of demons or avidya (a Sanskrit word meaning also ignorance, absence of wisdom) who appeared during a battle between divine and non-divine forces. In this context, Kali is considered the powerful form, or rather enraged, of the great Durga.

In India, as everywhere else, it is told that there has been a switch in the divine pantheon at the same time of the Aryan invasions that brought about male gods, celestial and fighters that superseded the previous pre-Aryan or Dravidian cultures dominated by the Goddess cult, linked to Earth and to feminine qualities.

The mythological stratification of pre-patriarchal and patriarchal eras is still legible in the Hindu divine pantheon, since the Goddess cult re-emerged such social changes in subsequent times, unlike elsewhere, and became even predominant in some centuries.

In a version of the origin of everything, Kali appears as the Great Mother Goddess generating every thing – in a form that evokes the Goddess of the pre-patriarchal cultures: before the Sun, Moon, Earth and other planets were created, when there was only and still darkness, the Mother, the Formless Maha Kali, became whole with the Absolute, Maha Kala. From their union, manifestation originates.

|

|

|

|

|

STORIES and MYTHS

Who is Kali? Myth about the origins of Kali.

Among many, the most widespread myth is the one in which Kali appears during the battle infuriating the deva and the demons, particularly between Durga and the demons, when Durga meets a demon that she herself cannot overcome, since at any of its blood drops touching the ground, another demon – or more than one – is generated, and they’re ready to battle. At that moment, from Durga’s frowned eyebrow (or – as in other versions – from the united energies of deva) Kali manifests as the Goddess able to defeat such enemy by drinking its blood as it is shed.

This is an important element: when everything is lost, when all forces, even divine ones, are not enough and defeat appears inevitable, at that point Kali emerges, the face of the Great Goddess that fights and wins over that demon, that danger. However, Kali is also the warrior entering the battle with no ability to distinguish between the good and the evil, between deva and demons. Her destroying force is hurled beyond any law or rule: the more she fights, the more she gets strong and drunk with her enemies’ blood so that, even when the battle is over, Kali continues her dance of death by killing anyone that gets on her way, appearing unrestrainable. The scared deva ask for Shiva’s help, as consort of the Great Goddess and therefore also Kali’s, and we’ll see later how he manages to calm her down.

Kali has explicitly in herself the double face of extreme rage: she’s the only energy that can protect whilst any other form of protection is useless and at the same time is no longer able to target for she is completely blinded.

As it often occurs with goddesses of the Hindu pantheon, Kali’s being energy and action is a vital aspect: without her even the God is motionless and lifeless.

Myths and stories about Kali

In myths and legends, Shiva somehow manages to soften Kali. It is interesting to know that there are numerous versions on how this happens, unlike the original myth, often offering fewer variants. Several stories show connections and roles of females in India, roles to which Kali is summoned up by Shiva. Others instead show how creative forces can transform furious power into positive and transformative energy. Other legends referring to her reappearances demonstrate instead situations in which She was called to manifest herself.

Shiva goes to the battlefield where Kali rages unstoppable and turns into a small child, hiding among the injured and the dead. Kali, advancing forward, stops in front of him, is pervaded by that universal feminine motherly instinct that transforms her into the fair Goddess, from whose bosoms flows the milk for the child. She is the Mother.

In the most widespread myth, with the intent to stop her, Shiva lies down on the battlefield at her feet, and she ends up on him, seeing him and recognising him. There are two variants of this version: on the first one, Kali suddenly realises that she was about to step on her husband, she gets scared and withdraws herself. Here, her role as wife is highlighted, which emphasises her submission as wife to her husband – both socially and culturally – typical of the Indian society. On the second more tantric version, Kali recognises Shiva at her feet and, by climbing on Him, she’s driven by sexual desire and starts making love to Him. The bellicose force is transformed in erotic energy. In some version of the tantric cult, it is the priestess – meaningfully better if menstruated – that joins with the devotee transforming him in this union, awakening his kundalini and leading him to his spiritual attainment.

In other stories, Shiva finds a way to dissuade Kali from her destructive dance by confronting her. In one, He stands in front of Her, laughing at Her and mocking Her for Her ugliness. She reflects in Him, acknowledges Her appearance, bathes Herself and turns shiny. In another, He invites her to a contest of movement and unrestrained dance, to a point in which She gets ashamed of exposing her private parts and, surprised, sticks out her tongue (apparently a 19th century version).

But not all stories read about Kali on the battlefield: in one story She quarrels with Shiva, Her husband, and furiously walks away from Him. She returns to Him convinced by the sage Narada and, while approaching Him, She sees a Goddess in His heart through a ray of clear light. That’s Herself, but Kali isn’t aware of having abandoned her “dark” form already and thinks at first that it is another goddess, and feels jealous. Once the misunderstanding is clarified, She’s given the name of Tripura-Sundari, the Beautiful of the Three Worlds.

In villages, many Kali-like goddesses’ stories are told, seemingly about victims of tragedies whom later transformed into the furious Goddess: often, it was about violence and abuse vindicated by Kali’s arrival.

Many of Kali’s stories tell us how She appears when a law is breached. The Mahabaratha was mentioned already, when Kouravas inflicted to Draupadi, Parava’s wife, the shame of being dragged at the centre of the room while wearing her hair down, and enduring the removal of her clothing, act that was avoided thanks to her ever-extending sari. From then on, Draupadi turns into Kali, until revenge is accomplished.

CULTS and RITES

Cults and rituals of Kali in India.

Far from a minimally exhaustive research in this field, I’ll introduce you here to some aspects of Kali’s vast cult, hints that made me reflect or taught me something.

|

|

|

In Tantrism, after all, the principle lies on the ability to recognise one’s own dark side through Kali. Each one of us has a Kali in ourselves, and the devotee is open to acknowledge in Her that darkness belonging also to him/herself. By doing so, the devotee leaves social and cultural orders, the surface, to enter the deepest Self. “Pure” action and righteous behaviour cannot accomplish the task of redemption from the material samsara, neither can they guarantee protection of the spirit.

The tantric way goes through all impure and degrading actions – those actions that bramhana vaishnava would never do. All taboos are infringed, with the way leading to death, blood, rot. It invites to acknowledge these in ourselves so that we can stand in front of Kali, head-up, maybe finally recognising to be a sparkle of the same energy.

In bakhti, the devotee stands by Kali like a defenceless, totally helpless child. He turns to Her as a Mother, and recognises Her as such in all Her forms, even the most terrible one. He sings praises and aims his adoration to Her. Love and trust flow, even in the event of a destruction, which the bakhta embraces as returning to Her. The availability to sacrifice, the complete acceptance of Her death powers result in the equilibrium between the polarity Goddess of Life / Goddess of Death, which are perceived as One.

Many gurus of the past two centuries belonged to the bakthi power, which often absorbs some aspects of Tantrism, among whom Ramprasad, Ramakrishna and Vivekananda.

Can mercy be found in the heart of She who was born from stone?

Wasn’t it Her who remorselessly trod on Her lord’s chest?

Men call you Merciful, but there is no sign of mercy in you, Mother.

Your chopped the head of others’ children, and out of them made the necklace you wear.

It doesn’t matter how many time I’ll call you “Mother, Mother”, you hear me but you won’t listen.

Ramakrishna

Stars are obscured,

Clouds cover other clouds,

It is resounding, vibrating darkness,

In the roaring wind that whirling blows,

Are the souls of a million fools,

Just escaped from their prison-home,

Trees lifted from their roots,

Swept away from the road.

The sea joined the scrimmage

and swirls gigantic waves

reaching up to the pitch-black sky.

The twinkle of a dim light

Reveals everywhere

Thousands and thousands of shadows

Of death, filthy and gloomy.

Spreading calamities and pain,

Dancing mad with joy,

Come, Mother, come!

Because Terror is your name,

Death is in your breath,

And the vibration of each of your steps

Destroys a world for ever. Come, Mother, come!

The Mother appears

To those who have the courage to love pain

And embrace the form of death,

Dancing the dance of Destruction.

Vivekananada

In many parts of India, as mentioned, Kali – or a Kali-like goddess that shares some of Her iconographic aspects – is the other face, the dark one, of the dual Goddess. The twofold Goddess is venerated in villages scattered around India, usually represented by a simple orange, red or deep yellow stone, on which two metal eyes are painted. Perhaps the idea is that it simply represents the face of the Goddess, whose body is represented by the entire village. Once a year, in autumn, the Goddess shows herself as the blood-thirsty Kali, to whom a male buffalo is usually sacrificed. During this ceremony, women let themselves go to hysterical manners and to the expression of hidden emotions, while men walk on fire, blood flows and pain is experienced. The wild side takes over, rage is expressed.

In Indian villages and countryside, the veneration once a year of the Goddess as Kali represents a primitive time (and place): the time and place of cry, of pain, of possession, of wild dancing, of blood sacrifices. A repetitive and limited time is offered to Kali – that time every year – delimiting the space inside the village, within which Devi is the only queen. Kali’s murti are installed in the outside. The Goddess lives in the outer wild.

In Kali’s cult, grief finds its full expression, especially in women, and a blood tribute is paid with animal sacrifices – formerly human, later banned by the English. Precise limitations open and close the rite. Within, boundaries disappear, energies erupt, what needs to be accomplished is fulfilled. Outside the order, the action in the rite has no karma. The order and what’s outside define each other. They both belong to the Goddess who encloses everything.

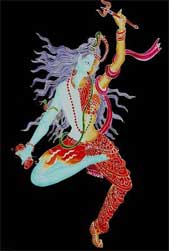

To Kali, a Katakali dance from Southern India:

SOME GODDESSES CLOSE KALI

There are numerous “Kali-like” goddesses, sharing Her aspects, energy and part of myths and stories, from different geographic areas and from different periods.

We’ve seen that in Hinduism, a common factor among different schools is a language made of rites, images and symbols associated to each divinity, clearly defining the scope of religious language, which is, in fact, mostly iconic.

One of the most popular one, shared in Buddhism, is Tara in Her wrathful form.

Tara in Her wrathful form

Tara belongs both to Hinduism and Buddhism; numerous wrathful feminine figures are found in the latter.

Tara belongs both to Hinduism and Buddhism; numerous wrathful feminine figures are found in the latter.

Tara is the main feminine deity venerated from the 5thcentury A.C. onward; she is rooted in several more or less “minor” forms both in the Hindu areas and in local cults preceding the diffusion of Buddhism, which it incorporated. Among her 21 original forms, Tara also includes at least ten irate representations, some of which are very similar to the Indian Kali. In these cases, her icon is often showed to fewer, since a specific initiation is required in order to contemplate her in meditation, which confirms the danger of her energy; nevertheless, her aim is to protect, to defend against the external and internal enemies of those walking the path of meditation.

As mentioned, Tara isn’t the only wrathful Goddess in the Buddhist world.

In one of the visits to the Tibetan Gompa in Pomaia, I noticed in a corner of one of many altars a figurine wrapped in fabric, unmistakably one of the furious goddesses: black, the red tongue out, a crown of skulls, a skeleton full of blood used as goblet.

It was Palden Lamho, Goddess of uncertain origins and of similar iconography to Kali’s, even with her own curious characteristics, like the riding of a mule. She is considered the Dalai Lama’s protector.

Hathor – Sekhmet

Sekhmet’s myth is told with a story similar to Kali’s. It tells when the God of the Sun, Ra, sent for the Goddess Hathor’s help (the cow Goddess of fertility, among other qualities) because a group of men receded on a mountain were plotting to kill him. Hathor turned then into the lioness Sekhmet, attacked and killed them. But she liked the taste of blood so much that she evidently wouldn’t stop killing. So, to stop her destructive rage, Ra mixed up some red ochre with barley beer and gave it to her. Sekhmet appreciated the drink very much, drank plenty of it and only after getting drunk she returned to be as sweet as Hathor.

In other versions of the myth, the gods decided to pour enormous quantity of red wine or red beer into the Nile, which coloured up so as to appear a bloody river. The Goddess, who dozed off, wakes up feeling blood-thirsty and starts drinking from the river until she gets drunk, hence why plenty of red beer flows at New Year’s parties.

Anat

Anat is a warrior Goddess from the Ugaritic culture popular from 2,000 to 1,200 B.C. circa, adopted later by Egypt, where she became the patron Goddess of the Pharaoh. She shares the passion for blood and the jubilation for killing with Kali and Sekhmet. Like Kali, she is described with many arms and heads. In myths, she behaves in a masculine way, for she belongs to an already patriarchal society, and enjoys killing especially those who deride her by sustaining that arms are not suitable for women. Usually her task is to protect Baal, her brother, god of rain and storms, for whom she nurtures a great passion. She incarnates a principle common to many other goddesses of the Middle East: Anat personifies a very high level of energy that can manifest both as erotic energy and warlike energy, in ecstatic passion of sex and of war.

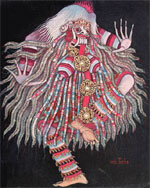

Rangda

In the contemporary Balinese mythology and probably directly deriving from the Indian Kali, we find Rangda, an example of furious Goddess, who represents the union of warlike characteristics similar to Sekhmet’s and Kali’s, but also many “damned” goddesses’ traits like the habit of attacking infants.

Rangda looks terrifying, with huge protruding round eyes, large saggy breasts and the red tongue hanging from her mouth at almost knee-length. Her mouth is bristling with teeth and bendy fangs, she has clawed nails and long ruffled grey hair.

It’s important to note that in the Balinese culture the sky is divine while the sea is demoniac, as in the best patriarchal tradition. Rangda is probably the heir of a pre-Hindu goddess of the sea turned into a demon the same way that often occurred in history at the changeover with patriarchal cultures.

Research for https://www.ilcerchiodellaluna.it © 2008

Edited on the website www.ilcerchiodellaluna.it in November 2008

______________________________

Notes:

(1) Devi, from the Sanskrit root dev, which means “bright”, from which Devi, Gods, and Deva, Goddesses, derive. The root dev is the same from which words like diva, divine, etc. come from.

(2) The Murti is a manifestation of the Goddess or God: it’s the Goddess or the God themselves that manifest through matter, being it stone, wood, metal or else. In the Hindu world, images of various divinities transform into murti through complex and very ancient rituals, in which the Goddess or the God is gradually invited – through calling or evoking – to epiphany.

(3) In threefold Goddess’ temples, Kali manifests herself in her kinder form, still associated to arms and battle but without her tongue sticking out, and is venerated without animal sacrifices, which are replaced with fruit and flower offerings, as the vaishnava tradition requires: here the dominant aspect of Devi is the one given by Lakshmi.